A paper recently came out where me and coauthors demonstrate that generative adversarial networks (GANs) can be used to estimate cloud vertical structures based on incomplete data. In the paper, we briefly argued that GANs should be applicable to many problems found in atmospheric science and remote sensing. As a first entry to this blog, I hope to use this post to elaborate a bit more on these points, arguing that GANs are a particularly interesting, yet so-far barely explored, tool for atmospheric science remote sensing applications.

Typical Features of Atmospheric Problems

To get started, let’s take a look at a few near-universal and widely recognized characteristics of atmospheric remote sensing problems:

-

We need to make inferences from incomplete data

With atmospheric measurements, there is almost always something missing. With in-situ instruments, the spatial coverage of the measurements is limited. Conversely, with remote sensing, we can get observations over a much wider area, but the interpretation of the remote measurements is more or less uncertain. So we can basically never get an accurate measurement — much less predictions — of the state of the atmosphere. The best we can do, then, is to think of the probability distribution \( p(\mathbf{y}) \) of some atmospheric state \( \mathbf{y} \), or the conditional distribution given an observation \(\mathbf{x}\): \( p(\mathbf{y}|\mathbf{x}) \).

-

The data has a complex spatial distribution

Atmospheric remote sensing problems usually deal with 2D or 3D data (maybe 4D, if you include the time dimension). The probability distributions of the various elements of these data structures are anything but independent, even though we often deal with them as if they were. The joint distributions can be incredibly complex, with intricate spatial structure, often owing to the various physical processes leading to self-organization in atmospheric fields.

-

The mean solution is often a poor one

We usually approach solving a probabilistic problem by trying to find either the mean solution or the most likely (i.e. maximum likelihood) solution. But with complex spatial structures, the mean solution tends to blur out the details, resulting in a solution that doesn’t look anything like a realistic example of the field we wanted to solve for (this is equivalent to saying that the root-mean-square loss leads to blurred details). The most likely solution might be a realistic one if we handle the probabilities properly, but given the complex joint distribution, that’s a very big if.

What’s a GAN, Then?

A GAN is a neural network that learns to generate samples that resemble its training data. More precisely, it’s a combination of two neural networks, the generator and the discriminator. The generator takes random noise as an input and transforms it to fields that resemble training examples (say, images). The discriminator is trained to distinguish real samples from those created by the generator, and the generator is simultaneously trained to fool the discriminator as often as possible. This competition between the two networks is called adversarial training. GANs were only invented in 2014 and have developed extremely rapidly since. Take a look at this study generating fake human faces in high resolution, or this list of other cool applications.

A relatively straightforward extension of the GAN is the conditional GAN. In this variant, we feed the generator and the discriminator some conditioning variables in addition to the random noise. These are something we already know about that particular sample, for example a measurement.

So why are GANs Useful for Atmospheric Problems?

Convolutional neural networks have shown unprecedented ability to learn complex spatial patterns. Meanwhile, GANs are inherently probabilistic: They map a relatively simple probability distribution to (an approximation of) the complex probability space of our data. Therefore, I think that GANs have a lot of potential for transforming how we solve atmospheric science and remote sensing problems because conditional GANs based on ConvNets can solve spatially complex inference problems in a probabilistic manner. We can generate spatially realistic solutions without sacrificing our ability to treat the errors in our prediction.

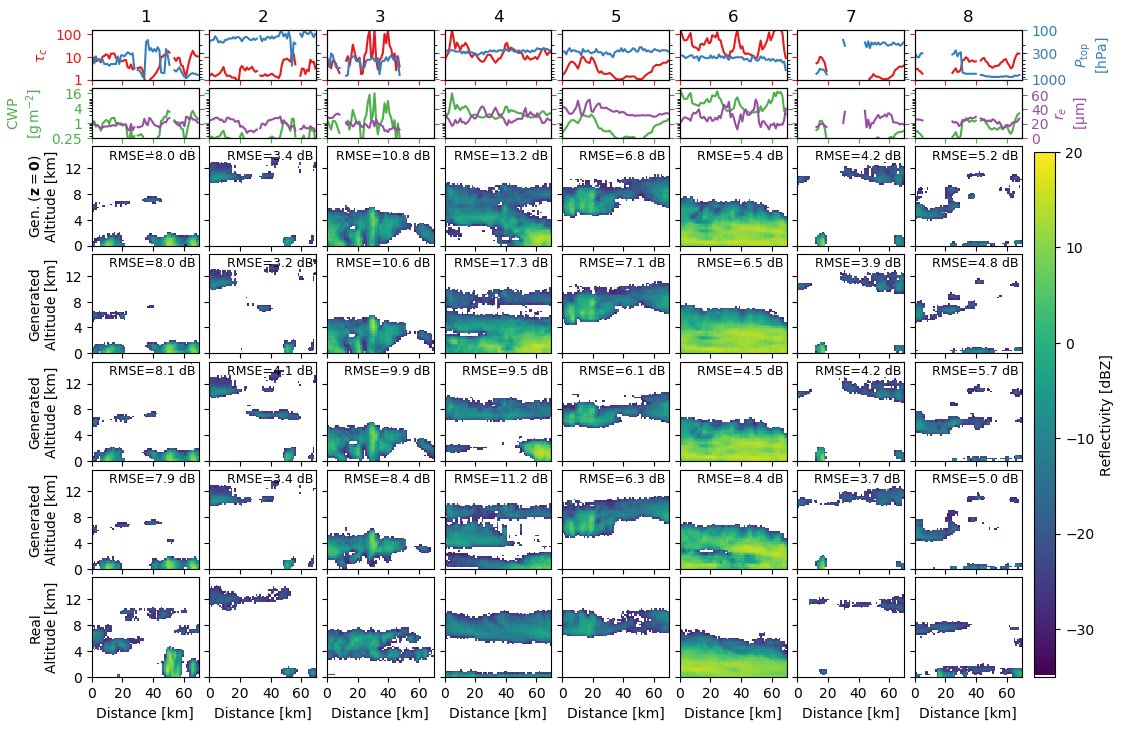

The image below is similar to those shown in our GAN paper: The bottom row shows real cloud vertical profiles as measured by the CloudSat satellite radar, while the rows above are guesses by the GAN as to what the vertical profile might be in the same case, given a few measurements from an optical cloud-observing instrument. Even though the guesses aren’t always perfect, the generated images look very realistic!

Now, that said, with GANs we need to adopt a different way of thinking about uncertainty, compared to what most of us are accustomed to. GANs don’t directly provide uncertainty metrics: There are no direct outputs of, say, the mean and standard deviation we’re used to. Instead, we need to approach uncertainty through sampling. We can generate many noise inputs for the GAN, and see what happens to the output. And if we really do want the mean and the standard deviation, we can in principle calculate those from the sampled outputs.

Another potential application for GANs in the atmospheric/climate sciences is unsupervised or semi-supervised classification of samples based on spatial structures. I hope to discuss this more in a later post. There are also several limitations and open questions related to GANs that are relevant to this problem domain, which also deserve their own post.